A soldier goes to war knowing he will not come back

Wellsville. Kan — Jim Butler hasn’t slept well since his son left for the war.

His wife, Cindy, has gone to bed. Hours of watching television for news about the war gave her a headache. But in a familiar ritual, she has perched a cell phone next to her pillow, just in case their son calls from Iraq.

Jim Butler sits alone in front of the television, and wonders what his son is doing at that moment on April 1. And he prays, like he does every night, that his son’s premonition is wrong.

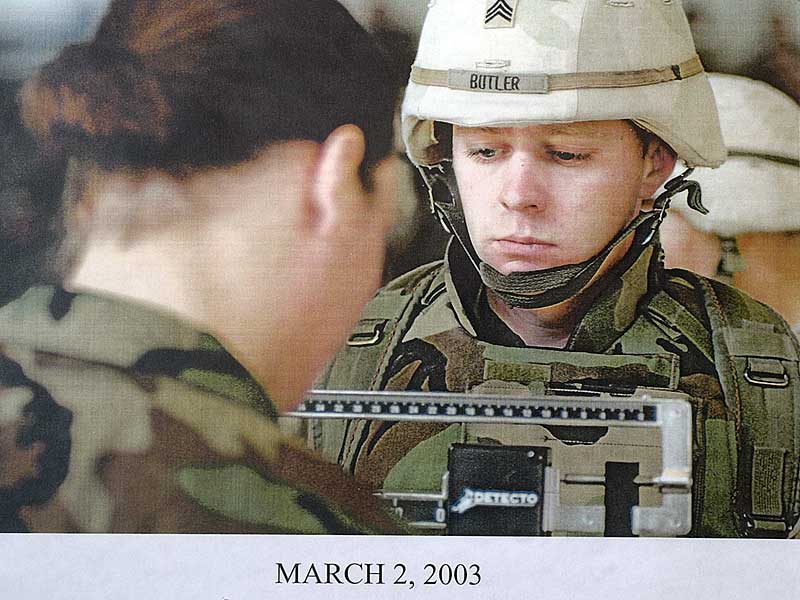

Sgt. Jacob Lee Butler deployed March 2. A week before he left, he told his father he knew his future.

The father and son were watching a movie, “We Were Soldiers.” Jake said he wanted music from the movie played at his funeral. He also wanted “Imagine,” by John Lennon, because it was a song about peace.

“Why are you telling me this?” Jim Butler asked.

Jake told him that he’d had a dream, in which he saw a family friend who had died years ago. The friend told Jake that he, too, would be in heaven soon.

“Dad,” he finally said, “I know I’m going to die in Iraq.”

Jim Butler couldn’t speak. Couldn’t breathe.

The father tried to comfort his son, reminding him how well-trained he was and how much common sense he had. But they both knew common sense and training couldn’t stop a bullet. Or a bomb. Or engineered germs.

Days later, when Jake told his father once more about his dream, Jim Butler knew what to say. “If anything happens to you,” he told him, “I will go to Iraq.”

He saw each of his five sons born into this world; he’d see the place where any left it.

“And that’s a promise,” he told Jake.

The 24-year-old, who was just hours away from his third deployment with the U.S. Army, looked up at his father and grinned. His father? The guy who at age 46 had never ridden on a commercial jet, who had never traveled outside the country, traveling to Iraq?

But, in that moment, the son knew how much his father loved him.

Jim Butler doesn’t tell his wife about Jake’s premonition, or about his own promise; she’s worried enough already. He keeps it all to himself, a secret pact between a son and his father. A promise he hopes he’ll never have to keep.

It’s 10:30 p.m. on April 1 when he hears car tires crunching on their gravel driveway. He peers out the window. A car’s headlights shut off, and its interior light clicks on.

He sees two persons in military uniforms.

And he knows.

He knows before the second car door slams shut: His son is dead.

Final goodbyes

Just three days earlier, Jake had called. I’m getting shot at, he told his sleepy mom. “I hope you’re shooting back,” Cindy Butler answered.

He told his father that his boom box burned up from the heat and sand and asked if he could send another.

His dad told him how everyone was thinking of him. How he was missed. How his 3 year-old nephew, Jess, was still talking about wearing his Army helmet. How his two nieces, too young to write yet, begged their mom to send him cards. How his four brothers, including his twin, Joe, asked about him daily.

Just before their connection was broken, he told his father he loved him. Cindy grabbed the phone and asked him if he needed a care package of toilet paper. He laughed once more and wanted to know how she could possibly know that. Then he told her he loved her, too.

It was the last time the parents talked with their son.

He was shot dead April 1 in an ambush in As Samawah, Iraq, during the coalition’s push toward Baghdad. The first Kansan to die in Operation Iraqi Freedom, he died a war hero, saving others. Eventually he would be awarded a Silver Star and a Purple Heart.

It takes two weeks for Jake’s body to arrive. At the funeral home, his family asks to open his coffin.

The son and brother they loved so much is dressed in a crisp uniform, nothing on his feet except black socks.

The day he left for Iraq, he looked burly, especially when he loaded up with all his gear. Although he was just 5 feet 5 inches tall and 112 pounds, he could carry a pack that weighed almost as much as he did.

But now in death, he seems little again. His head and face are swathed in bandages. Beneath the cloth his nose is swollen and bruised.

Cindy Butler asks the funeral home director to remove one of her son’s white military gloves. She wants to hold his hand one last time.

But as the tape around the glove is removed, she sees that his hand, like his entire body, is sheathed in form-fitting plastic. She pats his hand without holding it, and whispers to him, “I love you.”

Then the coffin is closed.

Jake’s funeral is exactly as requested. His favorite songs are played. Brig. Gen. Frank G. Helmick speaks. Everyone sings “America the Beautiful.” And the service ends with a bugle soloist playing taps.

Afterward, flowers arrive, and dozens of friends and neighbors take food to the Butler home. Stacks of cards and letters fill their mailbox. Several letters come from the highest politicians and military officers in the United States.

Throughout the summer, the Butlers receive something through the mail from their son, either letters that he had mailed, or care packages that were returned. Each time, Jim Butler says, it feels like Jake telling his family he’s thinking about them.

In July, Jake’s video camera arrives. He had recorded the war’s opening moments from inside his Humvee. Jake, a sergeant, was the truck commander for the Humvee, the one who communicated on the radio, the one who made the quick decisions.

The video shows him and his men crossing into Iraq from Kuwait. The camera also scans inside the Humvee, where a small homemade pine box is wedged in by the gearshift. The box, protecting his boom box, was built by Jake and his father before he deployed. The last item the camera focuses on is a closeup of the Humvee’s dashboard. There, a framed photograph is mounted, a photo of Jim and Cindy Butler, smiling, their arms around each other.

In August, a letter arrives from Iraq, dated April 1. The letter is the one that soldiers hope their families never have to read.

“Dear Mom and Dad,” the letter begins in the familiar handwriting. “If you’re reading this, it means I didn’t make it.”

No matter how many times Jim Butler reads this letter, his hand still shakes whenever he holds the paper.

“I love you very much. I will tell everyone in Heaven you said hello. I’m sorry to put you through so much….I’m sorry I can’t spell….”

Jake tells his parents to take his insurance money and, after paying off his debts, to buy themselves nice things. He tells his mom to buy herself a new car, his dad to buy more cattle. He wants his brothers, nieces and nephew to have a little of the money, too.

Then he tells his dad to go ahead and retire, he’s worked hard enough.

Jim Butler laughs through his tears at this sentence. “It’s not enough, Jake. Not enough.”

Jake was special, his father says.

“How could a man, knowing he won’t survive, still leave for a war? I don’t know very many men who would do that.”

Jim Butler clenches his jaw, more determined than ever to keep his promise.

Planning to go

Jim and Cindy Butler had never had a senator at their home, but Sen. Sam Brownback of Kansas calls weeks after the funeral and asks if he can come over.

For three hours the senator sits in the Butler living room and chats with them about Jake, their four other sons, the war, and then about Jim Butler’s promise.

“He was very nice,” Jim Butler says, “but he didn’t want me going. I told him what I tell everybody, I have to go, and I have to go now, to see the same Iraq that Jake saw. I don’t want to wait until there’s a McDonald’s there…. It’s my decision. My life.”

Brownback says he will try to help Jim Butler on his journey. There are others who want to help, too.

In late August, the Elves of Christmas Present decide that this father’s last promise to his son is an extra special case. A group of anonymous volunteers, the elves usually help families over the holidays.

The group’s leader is relentless in contacting politicians, who in turn call others they know. U.S. Sen. Pat Roberts’ staff members also spend hours talking with their military contacts. So does Rep. Jim Ryun’s office, which sends official letters of request to the secretary of the Army, the secretary of state and the U.S. Central Command in Florida.

Still, after weeks pass without any word, Jim Butler doubts anyone will help him. He knows that the stakes are high for anyone who assists him. If Jim Butler, the father of a slain soldier, is killed in Iraq, the decision to let him go could be second-g

And Jim Butler knows, too, that when people hear about his quest, they first judge him to be foolish, selfish or maybe even on a suicide mission.

None of this deters him. He makes his own plans.

“I was the one who made the promise,” he says over and over. “No one else did. I don’t expect them to understand this.”

He fills out travel documents and sends them off for a passport — which he needs to have for 90 days before he can apply for a Kuwaiti visa. He gets his travel shots. He makes out his will.

Each night, news broadcasts report more deaths of U.S.-led coalition soldiers. Iraq has become even more dangerous.

And then Jim Butler begins having his own dreams.

He tells no one at first. But in his dreams, again and again Jake visits him, and the father and son laugh together as they sit on top of a stairway.

They are good dreams, he says, because he gets to see Jake. Although he’s unsure what the dreams’ message is, he knows he must go soon.

As tender as he can, he prepares his heart-broken family that another Butler is going to Iraq — even if it may kill him.

Honoring a buddy

Jim and Cindy Butler rejoice when they hear that Jake’s platoon of cavalry scouts has arrived home from Iraq. They invite them all to their Wellsville home for a September barbecue, in honor of Jake.

Jim Butler also hopes they’ll tell him what happened to his son.

Around noon on a Saturday, cars and trucks begin lining their driveway. Every soldier who enters their home walks over to the Butlers and introduces himself. There are handshakes and hugs. Jim Butler leads them to “Jake’s wall,” an entire wall devoted to Jake. Photographs, medals, certificates, poetry, even a letter from President Bush are on this wall.

Each soldier stands silent, alone with his thoughts and memories.

One soldier, Staff Sgt. Alex Velasco, arrives later than the others. He looks uncomfortable, with eyes that dart around the room.

“I wasn’t sure if I should come,” he says later. “I didn’t know if I’d be welcomed or whether Mr. Butler would yell at me.”

Jake, he explains, saved his life — and may have died because of it.

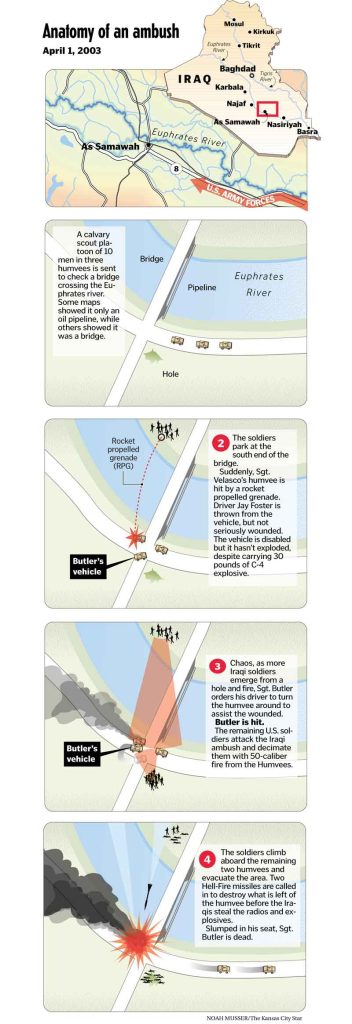

That day, April 1, the scouts were ambushed by dozens of Iraqi soldiers. Velasco’s Humvee was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. His driver was blown out the Humvee but wasn’t seriously injured. Velasco was hit by shrapnel. Their Humvee was disabled.

Jake, who was in the second Humvee, ordered his driver to pull alongside the first Humvee to rescue the wounded and shield them from the attack. But in the metal rain of bullets, Jake was hit. He died instantly.

The trip home from Baghdad was difficult for Velasco. As happy as he was to be returning home to his wife and his 18-month-old daughter, it didn’t feel right to be returning without Jake.

“I thought maybe Mr. and Mrs. Butler would hate me,” he says.

But in a moment, Jim Butler comes over and gives Velasco a hug. Velasco smiles, relaxing his lips from their hard, tight line. At the Butler home, on this day, the war with all its ugliness seems far away.

There is laughter from these young parents. A couple of the babies at the gathering were born while their fathers fought in Iraq.

Some soldiers play pool. Others tell war stories. At sundown, the Butlers gather everyone and ask them to untie the yellow ribbons lining their front porch.

It turns into an impromptu ceremony, a solemn moment. No one wants to untie the first faded yellow ribbon.

“We’re grateful you were with Jake,” Jim Butler says. “We’re proud of you. You guys done good over there. My door is always open to you.”

Then, he unties the first ribbon, handing it to a soldier. The others follow, taking down the rest.

The group members pile into their cars and trucks and drive to Jake’s gravesite, which is just a few miles from the Butler home. At Jake’s grave, the soldiers line up in a military formation, then drop to one knee.

They are young, clean-shaven, in sweatshirts and baseball caps. They all lift beers toasting their buddy. Jim Butler raises one, too, and then pours it over his son’s grave. As the sun chases the last of daylight from the sky, they each nod or salute his tombstone. Several blink back tears.

Doubts and hope

In Baghdad, Col. Russell D. Gold flicks on the fluorescent light in his tiny office.

The windowless room, probably a former janitorial closet, is just large enough for a cot, a desk and a computer. But now this former Arab Oil Ministries building is the headquarters for the 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division from Fort Riley, Kan. Gold commands more than 4,000 soldiers spread throughout the city.

Gold was in Kansas in April when Jake died. His orders were to deploy to Iraq once the troops captured Baghdad.When he heard about Jake, Gold went to be with the Butlers. Jim Butler told Gold then, just as he had told everyone else, about his promise to his son. But while others may have forgotten the father’s words, Gold couldn’t forget them. Since arriving in Baghdad on April 26, he has asked his superiors permission to provide security and to escort Jim Butler to the site where Jake died.

But again and again Gold’s requests are denied. Iraq is a hostile environment, superiors tell him. No place for a civilian. Terrorists hide homemade bombs along the roadways. Snipers shoot from the shadows. It would be too difficult to protect Jim Butler from harm.

Still, Jim Butler continues gathering the documents he needs to go.

Tonight Gold speaks with a man who identifies himself only as Chief Elf, the leader of the Elves of Christmas Present. He reiterates that Jim Butler has his passport, his Kuwaiti visa and a nonrefundable airplane ticket dated Oct. 9 — less than 24 hours away.

Jim Butler is going on his own. One way or another, this father is determined to honor his last promise to his slain son. Gold sighs at the news.

“If Mr. Butler tries to do this alone,” he says, “there is a 100 percent chance he will be killed.”

The “promise,” he says, is turning into a Greek tragedy, unfolding before their eyes.

In Wellsville, one day before Jim Butler is scheduled to leave, he gets a letter from Sen. Roberts. It isn’t good news. The senator regrets that his request to help Jim Butler was denied. An e-mail message arrives, too, from Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez in Baghdad. The military has also said Iraq is too dangerous now for a civilian.

Jim Butler isn’t surprised. He knows he’s ready to go solo. He’s made peace with God. Paid off his debts. Made a will. He sat with each of his four sons, his parents and his wife, asking them all to try to understand why this journey is so important to him.

One by one they tell him they support him. But they don’t want him to go.

The night before he leaves, Jim Butler takes his family out to eat. His bag is packed. In it are Jake’s military boots and two CDs.

“I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do when I get to the spot,” he tells them. “I guess I’ll know once I get there.”

Midmorning the next day his family takes him to Kansas City International Airport. His wife drives her new car bought with Jake’s insurance money. She picked a silver KIA because the initials can stand for “killed in action.” Her license plate is “S-Star.”

The plane begins boarding and it’s time for Jim Butler to go. Joe, Jake’s twin, cannot hold back his tears any longer. Justin, the youngest brother, weeps too. Josh and James stare at the floor. Cindy Butler bites her lip.

“I don’t want to lose you,” Justin tells his dad, gripping his father’s shoulders in an embrace. “I already lost my brother.”

When Joe hugs his father he tells him: “You don’t need to keep this promise ’cause Jake’s not here.”

Jim Butler embraces his wife last.

“I hope you find what you’re looking for,” she whispers to him as their eyes meet. She has given him a gold cross to wear around his neck.

He also wears an eagle charm that belonged to Jake.

Just before he disappears into the plane he looks back at his family once more. Four strong-hearted boys, a loving daughter-in-law, three grandchildren and a wife he adores.

He takes a window seat. As the plane roars off the runway, his fists curl tightly, then relax. Looking out the window, he presses his nose against it like a young boy.

“I’m doing what I’m supposed to do,” he says. “I’m not scared. I don’t know what’s going to happen. Or what I’m going to find.”

“I just know I have to try.”

A pledge finally is fulfilled

Capt. Randall Baucom from Camp Doha stands in the lobby of the Kuwait airport.

Just minutes earlier, his superior officer gave him orders to pick up Jim Butler, a father determined to visit Iraq. Butler had promised his son, Sgt. Jacob Lee Butler, that if anything happened to him, he would go to the spot where it occurred. And nothing is going to stop the 47-year-old Wellsville, Kan., man from honoring that promise.

Another group of soldiers, from a different unit – the 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division in Baghdad – also waits for Butler.

Both groups hold up signs: Mr. Butler?

Suddenly, the two groups see each other.

Baucom is angry, certain that someone has pulled a practical joke on the U.S. Army.

But this is no joke. A man from Kansas who identified himself as Chief Elf has worked behind the scenes since August, calling, sending e-mails and writing letters to politicians, private security agencies and military officers.

Although everyone is sympathetic to Butler’s desire, no one has committed to helping him. Chief Elf now fears that the Kansan is traveling to his doom.

But his calls were successful. Before Butler’s plane lands, the staffs of two different generals, one from Kuwait and one from Iraq, call him asking for the flight information.

So, here they are: two groups of U.S. Army soldiers looking for the same guy. But as they sort out the confusion, they see their man, obviously an American, lean, slightly bow-legged, wearing broken-in blue jeans, a flannel shirt and gym shoes, standing among all the robed Arab men and women.

Butler eyes them, too.

For a moment, he considers walking by them all without saying a word. Why would the military be here now? He’s already been told they won’t assist him on his trip to As Samawah. He fears they will force him to return to Kansas.

All Butler knows is that no one is going to stop him from fulfilling the promise he made to his son.

Not even the U.S. Army.

Dangerous journey

The Army has decided to let Camp Doha in Kuwait take responsibility for Butler. But at the airport Maj. Mark Holycross does the initial introductions because he’s from Fort Riley, Kan.

After traveling 29 hours through nine time zones, here was somebody from home. Butler smiles.

Baucom invites him to be a guest of the military at Camp Doha. Butler agrees, especially when he learns that his son had stayed there, too. He doesn’t know how important the next few hours will be: The decision whether the Army will help him or not rests with another officer, Col. Jeffrey Snow.

Snow’s orders are to meet Butler and determine if he is on a suicide mission or if he is just a dedicated, albeit naive, father honoring a promise he made to his son.

The two men talk for hours. About children. War. Loss. Promises made. Honor.

Butler tells Snow about his son’s dreams and the promise. About everyone saying they would help him and then, seemingly, no one helping him. He tells him he doesn’t hate the president, or Iraqis. He just wants to stand on the spot where his son died, play a little music, say a little prayer.

“A promise is a promise,” he tells Snow.

Snow makes his recommendation to Lt. Gen. Dave McKiernan. Helping this father is the right thing to do, he says.

The mission is on.

For two days the U.S. Army works on a threat assessment. Butler sits in on the meetings.

The dangers are many. Terrorists could shoot rocket-propelled grenades at the choppers, or they could stage an ambush on the ground. A thug sensing an opportunity might take the initiative to attack. Maybe someone would set off a bomb, or lob a grenade, or conceal a handgun until the last minute and fire at close range.

The different scenarios —- and ways to avoid them —- seem endless to Butler.

No soldier is ordered to go. But when Snow asks for volunteers, several dozen step forward.

The plan is to fly to As Samawah, a two-hour flight. Because of vegetation, everyone will have to hike two miles through brush and into the city to get to the exact spot where Jake died.

The father will have an hour on the site.

The soldiers warn him that Iraqi adults will be curious. Children will wave and smile, but the soldiers will keep them back a safe distance. One soldier will record the scene on videotape for Butler’s family to watch later.

On Monday morning, Oct. 13, Butler and dozens of soldiers stand on the tarmac at Camp Doha’s airport. Snow warns them again about the risks: “Be ready for anything,” he says.

Butler nods his head. They cinch him into a bullet-resistant vest. He slaps his chest a few times: 16 pounds of ceramic plates made to stop most bullets – but only if the bullet hits where the vests covers him.

His combat helmet is wrapped in camouflage material and feels heavy on his head. Its chin strap is tight, but still loose enough so he can open his mouth. Someone asks him if he feels like a soldier yet.

“Give me an M-16, then I will,” says Butler, who has never served in the military.

Just before they leave, Snow slips new batteries into his boom box. Butler clutches the two CDs of Jake’s favorite music that he’s carried all the way from Kansas.

The helicopters take off in a cloud of brown wash, blades whapping the air. From his headset, Butler can hear the pilot’s chatter with the control tower.

The convoy of helicopters swoops close to the ground. Butler watches the terrain of desert, scrub brush and low-slung mud buildings slide beneath them.

With all the hatches closed, no air moves inside the back of the helicopter where he sits. Butler’s bullet-resistant vest is cutting into his shoulders. He holds his vomit bag tight, willing himself not to throw up.

The ride includes a fueling stop at Tallil Air Base, about 30 miles from As Samawah. Butler keeps rehearsing in his mind how the mission is planned. His orders are clear: Listen and obey. Several soldiers will be guarding him. If something happens, Butler knows to run, or he may be slammed to the ground, protected by a soldier. They warn him that in every battle the only common theme is that it’s pure chaos. That’s why soldiers train so hard – so they won’t have to think, just react.

He knows he’s trusting them with his life.

Soon, the landing site is in view. The plan is for everyone to jump out as quickly as possible from the belly of the helicopter, then run to cover. A soldier stands in front of Butler. He jumps and runs. He feels another soldier’s hand on his back as he runs.

The helicopters zip off, their thumping fading into the distance. They will not return until the agreed time. The plan is to maintain radio silence, if possible.

It is quiet after the choppers leave. Soldiers surround him with their weapons ready to fire. No one talks.

Some soldiers walk in front of him, some on the side and some behind. They form a perimeter. Others are even farther out, eyes darting back and forth, noticing anything that is moving.

Everyone checks and double checks for danger.

Mixed into it all is the daily normal routine of a city with a population of roughly 124,000.

As they enter, there is noonday traffic. A Nissan pickup truck drives by. A horn honks from a white taxi cab with orange doors. A boy pedals by on a bicycle. A herd of goats scampers past the soldiers. A man in a robe ambles by. He lifts his weathered face and smiles at the video camera.

Butler squints behind his sunglasses. This looks like the pictures he’s seen of Vietnam, he thinks.

He walks stiffly, trying to keep the vest from pinching his back. Wearing jeans and a new Jake Butler memorial T-shirt, he stands out among the camouflaged soldiers.

He also wears his son’s desert Army boots, which are a perfect fit.

As he walks along the dusty road he takes in the images, with all its palm trees and tall grasses and legends. This is where many people believe is the birthplace of civilization.

Then Butler sees the mighty Euphrates, a wide muddy river. A tugboat moves slowly along its banks. He sees a metallic bridge he recognizes from a photo – a bridge with an oil pipeline running just underneath it. All the stories he’s heard about his son’s battle, all the soldiers he’s talked with, all the numerous diagrams and descriptions of what happened that morning six months ago – everything is coming together.

In the middle of the roadway is a blackened spot on the asphalt, a melted blemish. The spot where he is certain an Army Humvee was blown apart by rocket fire.

“This is it,” he says to Snow, who is scanning the coordinates of his Global Positioning System. Butler will not be able to stand on the exact spot where his son died because it’s right in the middle of the intersection.

Instead, he chooses a quiet area overlooking the river and the bridge.

He stoops down and places the first CD in the boom box. Snow turns the volume control to high. Then, the sound of bagpipes cuts through the noise of everyday Iraqi life. “Sgt. McKenzie,” one of Jake’s favorite songs, begins.

Butler looks out over the Euphrates and thinks about his son’s last moments. Tears roll down his cheeks. He’s heard the story so many times it’s as if it is playing now before his eyes.

Ambush

April 1, 2003: Coalition forces’ reconnaissance teams are looking for a western route to isolate the northern section of As Samawah. They didn’t want to take main roads.

But the Iraqis are clever. They keep them from taking alternative routes by building barriers that force them to take main roads.

The U.S. led-coalition forces press on toward Baghdad, skipping towns that have the enemy in them.

“Go fast. Go swift. Don’t stop to ‘clean’ out every problem along the way,” are the orders, says Capt. Rob Boone of the 82nd Airborne Infantry Regiment.

Traveling along these roadways are heavy weapon companies, which include .50 caliber machine guns, grenade launchers, a tank killer and a wire-guided missile. But the scouts, who travel much faster, have camped near As Samawah for two days, waiting for the heavy weapon companies, food, water and fuel trucks, to catch up.

Around noon, the scouts are given a mission.

“The problem,” says Maj. Dale Ringler of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, “was how do we get our logistical supplies to the north side of the river?”

The scouts are sent west to find a crossing site.

In the planning session, the Army’s intelligence said that bridge No. 2 was really just a pipeline. A map said otherwise.

Ringler says he has “to get eyes on it.” Is it a bridge or a pipeline, and can it hold the Bradley tanks?

Jake and his cavalry scouts set off in three Humvees. They drive down a frontage road near the Euphrates River and come upon the bridge. Alongside it is an oil pipeline.

The soldiers set up a T-formation with their Humvees, to check the bridge.

One moment everything is fine.

The next, chaos.

An Iraqi soldier fires a rocket-propelled grenade about 300 yards from across the other side of the river. It hits the first Humvee in the hood latch.

The explosion throws the Humvee’s driver out the vehicle. As he stands up he begins shooting at Iraqis, looking for cover. Staff Sgt. Alex Velasco, the truck commander, is bleeding from his chin and shoulder. His gunner, standing in the back of the Humvee, shoots back but Velasco can’t hear the shots; the explosion made him temporarily deaf.

Velasco’s Humvee is carrying 30 pounds of C-4 explosives that could detonate if hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. The soldiers are taking heavy fire from both sides.

“I’m hit! I’m hit! I’m hit!” someone screams into the radio.

A soldier who is nearby on a convoy mission hears the battle on his radio and relays it back to the tactical operations center.

At the same time, more Iraqi shooters dressed in civilian garb rush out of a hole near the bridge, firing off more rounds. This is not a rag-tag band of thugs, an officer will say later. These are highly trained soldiers who have been waiting to ambush Americans.

Jake, in another Humvee, sees what is happening and yells to his driver to back up and turn around. His plan is to shield the wounded men with his own Humvee and get them out of there.

One bullet hits Jake in his jawbone, but no one notices.

A third Humvee pulls around, and its gunner shoots, cutting many of the Iraqi men in two. He fires his weapon until it is hot to the touch and nothing on the ground in front of him moves.

Some American soldiers climb on top of one Humvee. There is no room to climb inside. Other soldiers climb on the other one.

After gathering up everyone, two Humvees drive away.

The battle takes less than two minutes.

Before they leave, they call for a helicopter to fire several .20-millimeter rockets to blow up the disabled Humvee. Iraqis are swarming over it, and the Americans can’t let the enemy take sensitive equipment like the radio or weapons.

A flash of light, an explosion, and the Humvee disintegrates. The scouts speed off.

At the 82nd’s aid station, emergency medical technicians help the wounded. When Jake’s door is opened, he slumps over and falls out. Immediately a medic puts a tube down his throat for an airway and tries to revive him. After 10 minutes, soldiers hear over the radio: “We have an American KIA.”

Sgt. Jacob Butler is now the 47th soldier killed in the war, the first soldier from Kansas.

His fellow soldiers wrap his body in a blanket. One medic takes out Jake’s bloodstained casualty card from inside his helmet. The card is a record of when a soldier died. The medic replaces it with a clean card so the family will never have to see Jake’s blood. Inside the helmet also was another picture of Jake’s parents.

The soldiers, still shaken, sit down and close their eyes, waiting for their commander, Col. George Geczy III, to arrive.

At first, soldiers aren’t sure what to do. “Where are the body bags?” asks Capt. John Gibson of the 82nd. No one knows.

Gibson drives a 5-ton truck to the aid station where Jake’s body is. The medical helicopter can’t land there, so the body has to be moved to a more accessible spot.

It takes 10 minutes for Geczy to arrive. The first soldiers he asks to see are the wounded. Then, with much dread, he tells his men: “It’s time to see Jake.”

He looks at the body, which soldiers are getting ready to take away. Geczy holds them back. He wants his men to grieve, even if it’s for a short time. He knows they need to.

Someone grabs the photograph of Jake’s parents from inside his Humvee and lays it next to the body.

Geczy looks at this young soldier, who just five hours earlier had complained that he wasn’t seeing enough action. He looks around at his men, then he begins to cry.

“Gentlemen, this is for real now,” he says. Their young faces are wet with tears and grime, sweat and, some, with blood. He begins a prayer searching for the words that might bring a little comfort to these soldiers.

“We’re thinking of you, Jake,” he says. “And your parents. We’re sad ….take care of us in Heaven like you did on Earth.”

He renames the upcoming battle for As Samawah, “Operation Stalwart Butler.” He encourages his soldiers to say goodbye to Jake one last time. When their private moments are over, Gibson and another soldier remove the body.

Gibson adds his own prayers, too. “It just didn’t feel right to pick him up without saying something,” he says.

They lift the body gently into the bed of the truck. Gibson stares at Jake’s face. He can’t get over how young he looks.

Jake was 24, less than a month from his 25th birthday.

Promise kept

Butler thinks of all these things as the music plays.

Traffic rumbles over the melted asphalt. The crowd of the curious has grown larger, with villagers standing confused and amused by an American standing on the side of a riverbank, playing music from a boom box.

At first, Butler doesn’t notice them. He stands tall, unashamed of his tears. But then his eyes rest on a little girl in a pink dress. She smiles sweetly at him and gives him a little wave.

“Imagine,” his son’s favorite tune because it’s a song about peace, soars on. Butler knows the time is almost up.

Snow asks him again, “Are you OK?”

Butler nods.

“A parent wants to take care of their children when they’re little,” he says, over the music, “but even after they’ve grown, you still want to.

“Sometimes you can’t.”

Then the music stops and the father’s promise is almost complete.

He reaches down and hands the first CD to Snow.

“I want you to have this for taking me here and helping me to do this,” he says.

But the second one with John Lennon’s “Imagine” he carefully puts back in its case. After finding a launch site, he plants his feet near the Euphrates and flings the CD with all his strength.

It soars out onto the river and skips across the water’s surface. The case opens. A circle glints in the sun before the CD plunks into the water with a tiny splash.

But its case floats away in the muddy water, bobbing downstream like a message in a bottle.

Lee Hill Kavanaugh, The Kansas City Star